Small Cities, Big Impact: Implementing Climate Action Plans

This is the final blog in a three-part series that presents the climate action planning and implementation process for three cities in Maharashtra. Read the first and second blog in the series.

Some of India’s biggest cities – Mumbai, Bengaluru and Chennai – have taken effective steps towards building their resilience against climate change by preparing Climate Action Plans (CAPs). Even relatively small and medium-sized cities in Maharashtra – Nashik, Solapur, Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar – have recognized their increasing vulnerability to climate change and developed working CAPs with WRI India’s technical support.

However, the best laid plans require effective implementation. Unlike bigger cities that have considerable municipal budgets, implementing climate action in smaller and medium-sized cities is a challenge due to lack of institutional structures and financing mechanisms. This blog looks at the pillars involved in the implementation of climate action plans, particularly in the context of three city CAPs supported by WRI India in Maharashtra. It looks at existing mechanisms that support implementation of such plans and identifies the gaps that need to be bridged.

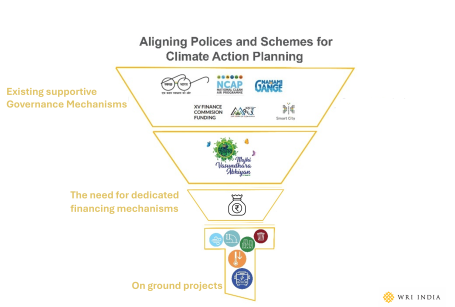

Nearly 75% or 38.7 million of the state’s urban population resides in the 43 cities under Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT). Concentrated efforts focused on these cities has the potential to shift the needle on climate action and help further India's ambitions to achieve net zero by 2070. While the AMRUT scheme is aligned towards urban services improvement, it also offers immense potential and opportunities for implementing and scaling up climate action in these cities. As these cities move from planning to implementation, three key pillars form the basis:

- Existing supportive governance mechanisms

- The need for dedicated financing mechanisms

- On ground projects

Existing Supportive Governance Mechanisms

National Level: India’s central governance structure is uniquely positioned to support state-led climate action. The Union and state governments support local climate mitigation and adaptation through schemes and missions such as Smart City, Nagar Van, AMRUT, Swachh Bharat and National Clean Air Programme (NCAP). Together these address interventions in climate and environment-related sectors, such as urban greening, water resource and wastewater management, solid waste management, and air quality.

State Level: At the subnational level, Maharashtra’s State Environment Department issued a Government Resolution (GR) on July 25, 2024, mandating the establishment of Climate Action Cells across 43 AMRUT cities, 36 districts and six revenue divisions of the state. This initiative is aimed at reinforcing climate action at the grassroots level, creating India’s first comprehensive climate-governance system that aligns actions and strategies to shape climate resilience at the state level. Initiatives such as Majhi Vasundhara Abhiyan (MVA) in Maharashtra focus on actions addressing climate change and environmental problems.

Local Level: At the local level, integrating central and state-led schemes can help mainstream climate action. This integration can be done by setting up an environment and climate change department at the municipal corporation level. The department can initially lead coordination across these multiple schemes. As it matures, the department can take on a more active role in project implementation and decision-making with the requisite budgetary allocation. In the case of Mumbai, the Environment Department at the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) was revamped into the Environment and Climate Change Department (ENVCC) entailing new positions, such as chief engineer and municipal architects.

Most schemes are sectoral, while environment and climate action are cross-sectoral and require coordination between different departments at the local level as well as collaboration across the center, state and city for achieving net zero targets. Robust governance mechanisms are even more critical for small and medium-sized cities that have limited capacity, budgets and resources.

Need for Dedicated Financing Mechanisms

Local governments in medium and small cities struggle to provide basic necessities, such as housing, water supply and road network, due to both limited budgets and lack of technical capacity. Consequently, climate action often takes a backseat. The current financing landscape in Nashik, Solapur and Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar is heavily reliant on central schemes and funds, as listed above, including the 15th Finance Commission (XV-FC). Another major challenge is a lack of creditworthiness in these cities, which restricts the opportunities for innovation and private investment in sustainable development.

Cities need reclassification, reallocation and fresh budget allocation for climate action, covering both adaptation and mitigation efforts. Projects more oriented towards climate action can be separately identified by a process called Climate Budget tagging. In the case of Mumbai, BMC launched the city’s first ever climate budget for 2024-25, delineating funding specifically for climate related work. Bankable climate-centric projects need to find commercial viability. The priority projects identified by CAPs can then be developed through early-stage project preparation for further implementation.

On Ground Projects

The CAP outlines strategies and actions across major sectors, including greening, urban heat, water resources management, waste management, air quality, energy and buildings, and sustainable mobility. Based on the vulnerability assessment and spatial mapping of hotspots, WRI India helped identify priority projects for the Nashik, Solapur and Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar CAPs in Maharashtra.

In Nashik, where flooding poses significant risks, the Godavari riverfront development was identified as a key area of work. One of the identified projects was rejuvenating the secondary rivers and enhancing the riparian buffer along the riverbanks using nature-based solutions, while creating a network of open spaces.

In the case of Solapur, due to the intense shortage of water and drought-like conditions, the focus was on wastewater management and reuse-related interventions through decentralized sewage treatment plants (STPs). In the case of Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar, air pollution was identified as a critical environmental risk in the CAP. Interventions targeted traffic hotspot mitigation, junction improvement and rainwater recharge structures along the major roads.

Coordinated efforts, in terms of supportive governance systems, identification of financial mechanisms and project development are key to implementing effective climate action. While robust climate policies and financial incentives pave the way, the groundwork lies in seamless collaboration between all stakeholders to implement projects essential to building a more resilient future.

Click to read the first and second blog in the series.